Diet and Stress: The Connection

Chronic stress has long been documented to have negative health consequences, supported by a litany of both observational and experimental studies. Remarkably, the effects of chronic stress on the body closely mirror those of a poor diet. But why do these two seemingly unrelated health challenges produce such similar outcomes? By reading this post, you’ll uncover a fascinating connection between mind and body—one you won’t hear about from any of your favorite health gurus.

Acute Versus Chronic Stress

What happens during a stressful event? The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is activated—often summarized as the “fight or flight” response. But in reality, the picture is more nuanced. Different stressors activate the SNS in different ways: exercise, exposure to heat or cold, and emotional trauma all trigger this system, yet the body’s adaptations to each are distinct.

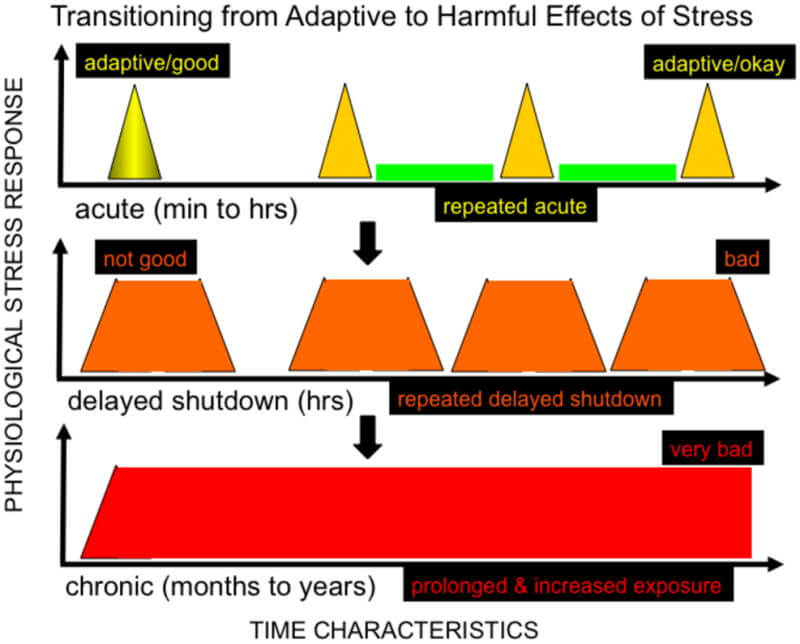

Acute stress differs from chronic stress in that the hormonal changes triggered by short-term stressors are temporary. In most cases, these acute responses resolve without causing harm. In fact, certain acute stressors—like exercise—can lead to beneficial adaptations that make the body more resilient to future challenges.

The primary driver of negative health outcomes is chronic stress—most commonly psychological in the modern world. Psychological stressors activate the SNS indirectly through the HPA (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis.

Mechanisms and Symptoms of Chronic Stress

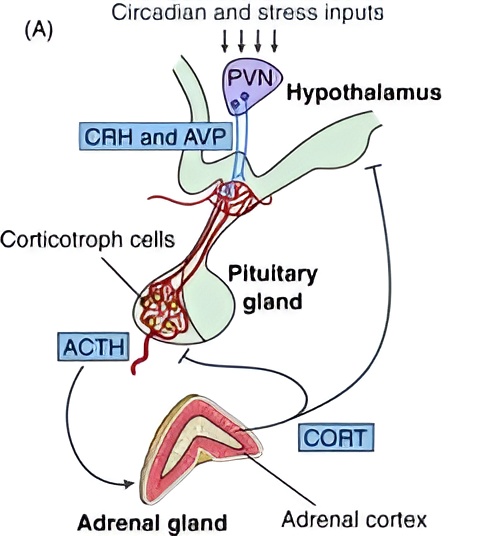

The paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus receives stress signals and responds by releasing corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and arginine vasopressin (AVP) into the pituitary gland. In turn, the pituitary releases adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into the bloodstream. ACTH then stimulates the adrenal cortex to produce glucocorticoids—the primary one in humans, by far, is cortisol.

These details explain what the diagram is illustrating, but the key takeaway is simple: stress leads to glucocorticoid release. And chronic stress? That leads to chronic glucocorticoid exposure. To understand the impact of this, we can look at patients with Cushing’s syndrome—a condition caused by prolonged glucocorticoid exposure, typically due to medication or tumors. Some of the key symptoms include:

- Elevated blood glucose and insulin resistance

- Accumulation of fat around the organs (visceral fat, aka beer belly)

- Weight gain and obesity

- Hypertension

- Elevated blood triglycerides

- Mood disorders

- Acne and other skin issues

- Osteoporosis

- Impotence/infertility

- Heart disease (if the syndrome is left untreated)

- Additional symptoms omitted for the sake of brevity

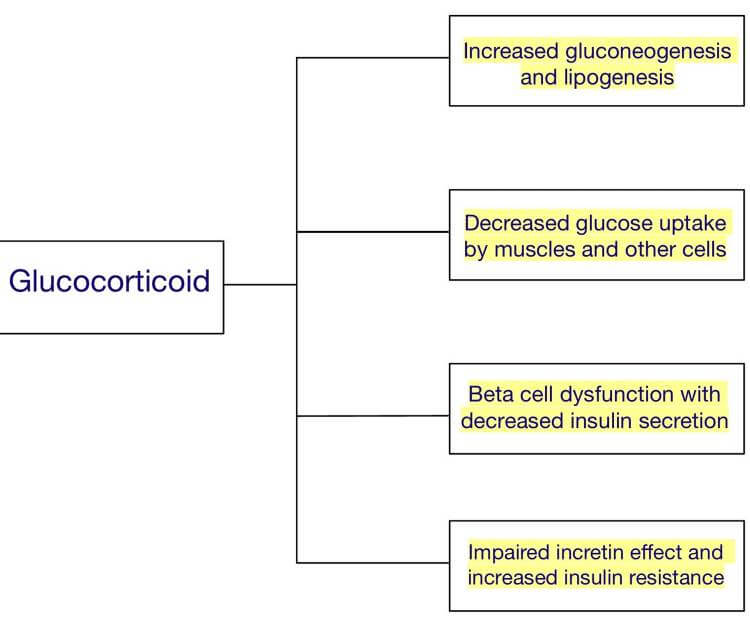

In fact, a specific name exists—steroid-induced diabetes—for a condition by which clinically-administered glucocorticoids can induce a diabetic state in a patient. Therefore, the idea that long-term chronic stress can also induce diabetes comes as no surprise.

It’s important to understand that cortisol naturally fluctuates throughout the day and doesn’t cause harm at normal physiological levels. Problems arise only with prolonged, elevated exposure. That means less cortisol is not inherently better—too little cortisol comes with its own set of issues. What matters most is maintaining cortisol within a healthy physiological range. Additionally, Cushing’s syndrome differs from more typical forms of metabolic dysfunction because it results from direct glucocorticoid exposure rather than from indirect exposure via the HPA axis. While not a perfect 1-to-1 mirror of chronic stress, it still serves as a useful reference.

Why Does Chronic Stress Have These Effects?

Consider the kinds of situations that likely caused emotional stress in early humans: food shortages, harsh environmental conditions, social instability, or threats from predators. All of these would have disrupted the ability to reliably secure food. The body’s response to such stressors reflects an energy conservation state—an adaptive shift designed to improve survival.

This would involve preserving glucose in the blood to prioritize fueling the brain rather than diverting it to the less-essential muscles, increasing fat accumulation as an emergency energy reserve, or suppressing reproductive function to conserve energy for immediate survival needs. These are just a few examples of how the body shifts into a survival mode.

Why Does a Modern Diet Cause the Same Symptoms?

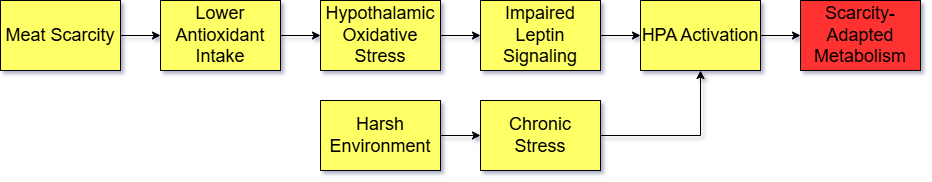

All energy production creates some degree of oxidative byproducts in cells. When a modern, high-oxidation diet is consumed—one that’s low in antioxidant defense nutrients like protein, specific vitamins and minerals, and other protective factors such as polyphenols or regular exercise—while being high in energy and oxidation-prone refined oils (Americans consume an average of 749 calories of refined oils per person per day), the result is significant cellular damage.

This is especially harmful to neurons in the brain that regulate energy balance and glucose metabolism. The brain is particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress, and some of this damage can be observed through inflammation in the hypothalamus. When these neurons prioritize repair, they become resistant to the satiety hormone leptin.

Leptin normally acts to suppress the HPA axis, preventing the cascade of symptoms associated with chronic cortisol exposure. But when hypothalamic neurons are damaged, the leptin signals from fat cells—signals meant to communicate that the body has sufficient energy—are no longer properly received. As a result, the brain is tricked into believing the body is in, or approaching, a state of food scarcity, triggering activation of the HPA axis.

Why Does This Make Sense Evolutionarily?

Historically, both a high-oxidation diet and chronic stress would have signaled that food scarcity was imminent, prompting the brain to initiate a suite of energy-conserving adaptations. Ancestrally, the foods easiest to store and preserve—nuts, grains, tubers, seeds, legumes, and honey—provided abundant energy but were relatively low in antioxidant nutrients compared to animal foods and fruits. In seasonal climates, hominins likely relied more heavily on these fallback foods during times when meat was scarce.

That doesn’t mean these foods inherently trigger negative metabolic changes. Rather, when they’re consumed primarily instead of secondarily to more nutrient-rich foods—as is often the case in modern diets—the ratio of energy intake to antioxidant defense becomes imbalanced. The imbalance becomes much more debilitating when the majority of food consumed is ultra-processed and almost completely devoid of nutrition; Americans consume nearly 60% of their energy in the form of ultra-processed food.

In other words:

So, including the aforementioned plant-based foods more strategically and sparingly—relative to animal foods and fruits—makes evolutionary sense. That said, the reason a plant-based diet, though nutritionally inferior in many respects, can still support metabolic health in the modern world is because many of its shortcomings can be mitigated with supplements and global access to a wide variety of plant foods. This allows plant-based advocates to construct dietary patterns that aren’t entirely dysfunctional—though still removed from ancestral norms.

Likewise, maintaining healthy stress levels adds to the support of a nutritious diet. Combining both physical and psychological strategies helps balance appetite, fat accumulation, blood sugar, blood pressure, and other physiological processes by ensuring HPA activation does not perpetually signal a starvation state.