Glucose Measurements and Why They Matter

Getting my annual blood tests is usually a disappointment because the standard panel—typically including tests like a basic metabolic panel or lipid profile—is sadly lacking for disease prevention, especially for conditions avoidable with healthy lifestyle behaviors. I like to request additional tests, either through my doctor or by ordering them online, and blood glucose measurements are the ones I’m most interested in. Here’s an overview of the important measurements, including their strengths and limitations. But first:

What Even Is Glucose?

Glucose is a monosaccharide, the simplest form of carbohydrate, which cannot be broken down into smaller carbohydrate units. It serves as the body’s primary carbohydrate-based energy source. More complex carbohydrates are digested into glucose, while other monosaccharides, such as fructose and galactose, are converted into glucose through metabolic pathways. Understanding glucose is essential because it plays a critical role in energy metabolism and is a key marker in blood tests for assessing metabolic health.

How Blood Glucose is Modulated

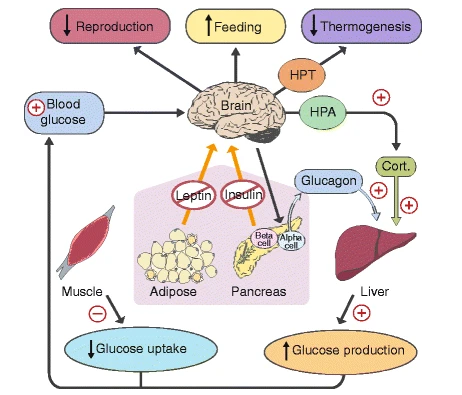

Blood glucose stability is important because both excessively high and low levels can lead to health problems. After eating, blood glucose rises, prompting the pancreas to secrete insulin, a hormone that facilitates the movement of glucose from the blood into cells for energy. During fasting or when on a low-carbohydrate diet, the liver helps increase blood glucose by increasing gluconeogenesis—a process that generates glucose from proteins and other non-carbohydrate sources. This dynamic balance between insulin secretion and gluconeogenesis ensures relatively stable blood glucose levels across varying dietary patterns. It’s important to understand that glucose tests do not measure sugar intake directly. Instead, they assess the body’s ability to regulate glucose levels.

From Health to Disease

In a metabolically healthy state, the pancreas responds to a rise in blood glucose by secreting the appropriate amount of insulin, allowing glucose to enter muscle, fat, and liver cells for energy or storage. However, when this system begins to falter, blood glucose regulation becomes impaired, leading to prediabetes, type 2 diabetes, and complications such as cardiovascular disease and fatty liver disease. A common misconception is that prediabetes marks the beginning of metabolic dysfunction. In reality, by the time prediabetes is diagnosed, underlying metabolic issues have often been present for years. Insulin resistance, the reduced ability of cells to respond to insulin, is a hallmark of this pathology and a key driver of disease progression. Alarmingly, 41.5% of U.S. adults are currently living with either prediabetes or type 2 diabetes, underscoring the widespread prevalence of metabolic dysfunction. Many more are likely to be living with some degree of insulin resistance, even if it hasn’t yet progressed to prediabetes. Beyond diabetes, insulin resistance is a significant risk factor for numerous other diseases, likely because poor metabolic health disrupts the ability of cells to efficiently use energy. When this fundamental process breaks down, cellular dysfunction occurs, paving the way for a variety of diseases.

What Causes Insulin Resistance?

The causes of insulin resistance are widely debated. One fascinating idea is that insulin resistance may be a deliberate adaptation by the body to prepare for potential food shortages. When food is metabolized into energy, reactive molecules called reactive oxygen species (ROS) are naturally produced. While ROS serve functional purposes in the body, excessive accumulation can damage cells. The body’s antioxidant defense system, which relies on proteins, vitamins, minerals, and polyphenols, protects against this damage.

However, a diet deficient in these nutrients relative to energy intake—combined with oxidation-prone substances like refined oils—can overwhelm the defense system. This imbalance particularly affects brain cells, or neurons, that regulate appetite and blood sugar. These neurons are highly susceptible to oxidative damage, and when damaged, their hormonal signaling becomes impaired. The impaired hormonal signaling leads to the following initial consequences:

In short, appetite increases, energy expenditure decreases, gluconeogenesis becomes more active, muscles develop insulin resistance, and various other changes occur. These adaptations explain why obesity is so strongly associated with insulin resistance and chronic disease. Historically, when energy intake was high relative to antioxidant nutrients, that may have signaled an abundant autumn harvest preceding a scarce winter. The body’s metabolic adjustments—increasing food intake and storage while reducing expenditure—maximized survival during hard seasons.

In modern society, however, where the imbalance between energy and antioxidant nutrients is both extreme and prolonged, these same adaptations lead to serious health problems. Insulin resistance is an indicator of metabolic adaptations that are inappropriate in today’s environment. This is why measuring it is so important, and fortunately, we have several tests to assess how insulin resistant we may be.

Fasting Blood Glucose

At my age and health status, this is the only test that my doctor orders by default. I’ll cite the Mayo Clinic here:

A blood sample will be taken after you haven’t eaten anything the night before (fast). A fasting blood sugar level less than 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) is normal. A fasting blood sugar level from 100 to 125 mg/dL (5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L) is considered prediabetes. If it’s 126 mg/dL (7 mmol/L) or higher on two separate tests, you have diabetes.

Under fasted conditions, there exists an expected range that blood glucose should fall into. An elevated level indicates some combination of insulin resistance and improper gluconeogenesis. However, blood glucose taken at any given point in time can vary significantly. As a personal example, on a particularly stressful day, my fasting blood glucose was measured at 98 mg/dL, which is considered to be nearly prediabetic. Three days later, a second measurement yielded a modest 81 mg/dL. This variation highlights how mental stress, as an evolutionary adaptation to physical threats, mobilizes energy by elevating glucose levels. For this reason, although a high fasting blood glucose can raise a red flag, additional tests should be used for more clarity.

Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c)

This test measures a long-term average of blood glucose. Hemoglobin is a protein present in red blood cells, and the percentage given by this test represents how much of that hemoglobin has glucose attached to it. Hemoglobin in red blood cells is continuously exposed to glucose in the bloodstream, so higher blood glucose concentrations increase the likelihood of glycation (glucose binding to hemoglobin). Because red blood cells have an average lifespan of three months, the hemoglobin A1C test reflects the percentage of glycated hemoglobin over that time. The Mayo Clinic considers an HbA1c above 6.5% to be diabetic, between 5.7% and 6.4% to be prediabetic, and below 5.7% to be normal. My most recent HbA1c was 5.2%. However, lower does not necessarily mean better; like all of these tests, HbA1c is primarily a tool to help identify one’s current state of metabolic health, rather than a marker to keep as low as possible in the healthy range.

While HbA1c covers the pitfall of a fasting blood glucose measurement being an instantaneous measurement rather than an average, it’s still a lagging indicator of metabolic problems for one simple reason: hyperinsulinemia precedes hyperglycemia. In other words, during earlier stages of metabolic disease, more insulin is needed to transport glucose out of the blood, but blood glucose measurements can still remain normal.

Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT)

Recommended in Peter Attia’s book, the OGTT requires an 8-hour fast as usual, followed by drinking a syrupy glucose solution. Blood samples are taken at consistent time intervals, and then the measurements of insulin and glucose in those samples are graphed over the next few hours. It’s among the most accurate ways to assess the body’s ability to respond to a carbohydrate load, thus painting a clear picture of metabolic health. The major downside is the test takes about three hours to complete, and the sugary drink may be unpleasant for some.

Fasting Insulin

Asking most doctors for this test may elicit a confused reaction. Unlike fasting glucose or HbA1c, fasting insulin does not have standardized thresholds for diagnosing prediabetes or diabetes. However, because hyperinsulinemia precedes hyperglycemia, an elevated fasting insulin can signal metabolic issues long before glucose levels become abnormal. Despite its lack of standardization in clinical practice, fasting insulin is inexpensive and worth considering as part of a broader assessment of metabolic health. Measuring metabolic health isn’t a binary decision of diagnosing diabetes; it requires understanding the continuum between wellness and dysfunction.

Although there is no universally accepted optimal level of fasting insulin, researchers have provided recommendations based on studies. A fasting insulin measurement can also be combined with fasting blood glucose to calculate HOMA-IR, which estimates insulin resistance. This paper suggests fasting insulin levels below 8 mU/L for men and below 10 mU/L for women, with corresponding HOMA-IR values below 1.5 and 2.0, respectively, as optimal. My most recent fasting insulin measurement was 3.1 mU/L, and my HOMA-IR, using this online calculator, was 0.6.

One limitation of fasting insulin, similar to fasting glucose, is that it can vary significantly between tests due to factors like stress, sleep, or recent dietary patterns. Nevertheless, fasting insulin, particularly when paired with HOMA-IR, offers valuable insights into metabolic health that may go undetected by glucose measurements alone.

Conclusion

Although these tests are traditionally used to diagnose diabetes, their utility extends far beyond that. They can help evaluate whether an individual is getting the proper nutrition to prevent the metabolic maladaptations triggered by a perceived upcoming food scarcity. While obesity is the most visible sign of poor metabolic health, lean individuals can—and often do—suffer from metabolic diseases while being mistakenly evaluated as healthy based on appearance alone.

Moving forward, educating doctors about the latest research into metabolic health will be crucial. By shifting away from a simplistic yes-or-no diagnostic model, we can develop a more comprehensive understanding of what the human body is doing and why. This approach will not only improve patient care but also help address the root causes of metabolic dysfunction, regardless of outward physical appearance.