Is Ozempic a Miracle Drug? The Hidden Metabolic Truth

Weight loss medications have entered a new era, delivering results so dramatic they’ve been hailed as miraculous. Demand is soaring, with everyone—from everyday people to billionaires—turning to these drugs in pursuit of weight loss. But are they truly the groundbreaking solution they seem, or just the latest chapter in a long history of fleeting, and sometimes risky, weight loss trends? Could hidden consequences be lurking beneath the surface, as with so many “miracle” solutions of the past? Let’s explore how these drugs work—and whether they live up to the hype.

Mimicking a Natural Hormone

GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), including semaglutide (the active ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy), liraglutide, and tirzepatide, work by mimicking a natural hormone called glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). This hormone helps regulate appetite and metabolism by slowing digestion, enhancing insulin release, and signaling fullness to the brain.

GLP-1 is secreted by intestinal L-cells shortly after eating, acting as a rapid satiety signal. However, its effects are fleeting, as natural GLP-1 is broken down within minutes. GLP-1 RAs extend this effect, suppressing hunger, delaying gastric emptying, and improving blood sugar control. By sustaining GLP-1 activity, these drugs have become powerful tools for both weight loss and diabetes management.

How Hunger Works

Hunger is a complex process regulated by multiple hormones and cellular signals. One key player in this system is AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), an enzyme that acts as an energy sensor within cells. When energy levels are low, AMPK adjusts cellular function to compensate.

For example, in muscle cells, AMPK increases glucose uptake and stimulates mitochondrial production, enhancing endurance and performance over time. This adaptability explains why repeated exercise becomes easier. When ATP, the cell’s primary energy source, is broken down into ADP and AMP, the rising AMP levels activate AMPK, signaling a low-energy state and triggering these metabolic adjustments.

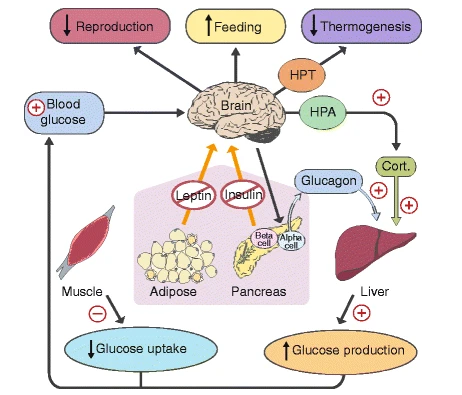

In the brain, AMPK plays a central role in hunger regulation. As an indicator of low energy, AMPK influences hunger neurons, prompting the body to seek food. Various hormones modulate AMPK activity, either increasing or decreasing hunger signals. For instance, GLP-1, a hormone released after eating, suppresses AMPK in hunger neurons, signaling satiety. Conversely, when GLP-1 levels drop, AMPK suppression decreases, allowing hunger neurons to become more active.

Other hormones, such as leptin (produced by fat cells) and insulin (released in response to carbohydrates), also suppress AMPK, signaling energy sufficiency. Together, these interactions create a finely tuned system that balances hunger and satiety, helping the body maintain energy homeostasis.

Why Do People With High Leptin and Insulin Still Overeat?

In theory, people with metabolic issues should have more than enough circulating insulin and leptin to signal a fed state, suppress hypothalamic AMPK, and reduce appetite. In metabolically healthy individuals, this system functions as expected. However, before obesity, diabetes, and other chronic conditions develop, the brain becomes resistant to these key hormones, failing to respond to their appetite-suppressing signals.

The root cause of this resistance lies in poor dietary choices that create an imbalance between energy intake and antioxidant nutrients. Normal energy metabolism produces oxidative byproducts, which must be neutralized by the cell’s antioxidant defenses. A high-energy diet deficient in essential nutrients—such as protein, vitamins (e.g., C, E, B vitamins), and minerals (e.g., manganese, zinc, copper, selenium, iron)—increases oxidative burden. Additionally, high consumption of oxidation-prone oils further exacerbates oxidative stress. The accumulation of these factors damages hypothalamic neurons, which are particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage.

When oxidative damage overwhelms cellular defenses, the body triggers an inflammatory response to contain the damage and initiate repair. As part of this process, glial cells suppress neuronal responses to insulin and leptin. This shutdown helps damaged neurons conserve energy and protect themselves from further stress—much like an athlete resting an injured muscle to prevent further harm.

While this mechanism may seem problematic today, it likely evolved as a protective adaptation in a very different environment. From an evolutionary perspective, this response—what I’ll call the oxidation response—may have helped the body anticipate seasonal food shortages. During periods of oxidative stress—whether from scarce food or poor-quality nutrition—the body’s adaptive response would have reduced energy expenditure, increased hunger, and preserved blood glucose to ensure survival. However, in today’s world of abundant, nutrient-poor food, this once-beneficial adaptation now drives obesity and metabolic dysfunction.

GLP-1 RAs Compensate for Leptin Resistance

Leptin resistance, driven by the oxidation response, reduces GLP-1 secretion from intestinal L cells. Research shows that leptin directly stimulates L cells to release GLP-1. However, when leptin resistance impairs this signaling pathway, L cells secrete less GLP-1, further disrupting appetite regulation.

Additionally, hypothalamic leptin signaling activates the vagus nerve, which helps maintain insulin sensitivity in liver cells. The vagus nerve also plays a key role in mediating GLP-1 secretion from intestinal L cells. Since leptin signaling activates the vagus nerve, it follows that oxidative stress weakens vagus function, further reducing GLP-1 secretion. In short, the same poor dietary patterns that promote excessive appetite, increased fat storage, decreased fat burning, and insulin resistance also contribute to abnormally low GLP-1 levels.

GLP-1 RAs offer a way to bypass leptin resistance. Their success mirrors what scientists in the 1990s had hoped exogenous leptin would achieve. Unlike leptin injections, which fail due to leptin resistance, GLP-1 RAs effectively lower AMPK activity in hypothalamic neurons. By bypassing leptin resistance, GLP-1 RAs restore appetite control and metabolic balance, making them one of the most effective tools for treating obesity and diabetes.

GLP-1 RAs and Addiction

Imagine an alcoholic who struggles to moderate their intake suddenly being able to stop after just one or two drinks. Numerous anecdotal reports, along with animal studies, suggest that GLP-1 RAs can reduce cravings and consumption of alcohol. This discovery carries profound implications beyond treating addiction with medication—it suggests that alcoholism and other addictive disorders may have metabolic roots. In other words, reducing addictive tendencies might be possible simply by improving metabolic health through lifestyle changes.

This animal study demonstrates how GLP-1 modulates brain activity, dampening activation of the mesolimbic dopamine pathway—the brain’s reward system—in response to alcohol, nicotine, opioids, and stimulants. Additionally, previous research shows that leptin, a hormone involved in appetite regulation, similarly reduces food reward-seeking by suppressing this pathway. The parallels between food reward-seeking and addictive behaviors are striking. Could the body’s adaptation to perceived nutrient scarcity—where increased pleasure from food is an appropriate response—be a primary driver of addiction? And if so, could a more nutrient-rich diet reduce addictive tendencies?

Indeed, researchers have found strong associations between substance use disorders and nutrient deficiencies. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean addiction stems from a single nutrient deficiency. Rather, this research supports the idea that metabolic changes—particularly those driven by oxidative stress—alter brain function in ways that increase susceptibility to substance abuse. These findings challenge the notion that addiction is purely a behavioral issue and suggest it may also be a metabolic disorder, with profound implications for treatment and prevention.

Do GLP-1 RAs Really Solve Obesity?

GLP-1 RAs alleviate symptoms of metabolic dysfunction but do not address the root cause—nutrient-poor food choices that lead to oxidative stress. However, reducing weight and improving blood sugar control—even without fixing the underlying issues—still provides significant benefits. Since metabolic dysfunction itself worsens health outcomes, alleviating it is still a meaningful improvement.

While GLP-1 RAs can induce substantial weight loss, their effects are often temporary. One study found that patients regained two-thirds of the weight they had lost within a year of stopping semaglutide, even with diet counseling and exercise. This suggests that unless patients remain on these drugs indefinitely, long-term weight management requires a greater emphasis on food quality.

The diet counseling in the study primarily focused on calorie restriction, an approach that often fails over time. A more effective strategy would prioritize nutrient-rich foods rather than mere calorie reduction. With the right food choices, a calorie deficit would occur naturally, making sustained weight maintenance far more achievable.

Other Dangers

GLP-1 RAs can be effective for weight loss and metabolic health, but they come with potential risks. Reported side effects include:

- Gastrointestinal discomfort (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea)

- Constipation

- Skin sagging due to rapid weight loss

- Acute pancreatitis

- Stomach paralysis (gastroparesis)

- Loss of muscle mass

- Malnutrition due to reduced appetite and gastrointestinal side effects

- Thyroid tumors were found significantly in rodents, but not in humans (so far)

Though some of these risks are mild, others—such as gastroparesis, pancreatitis, and muscle loss—may have serious long-term consequences, particularly if GLP-1 RAs are used indefinitely without addressing underlying dietary and metabolic issues.

Conclusion

GLP-1 receptor agonists represent a powerful tool for weight loss and metabolic improvement, but they are not a cure for obesity. While they effectively suppress appetite and override leptin resistance, their benefits are often temporary, and long-term reliance comes with potential risks. The root of the problem—nutrient-poor diets that drive oxidative stress and metabolic dysfunction—remains unaddressed. Sustainable weight management requires a shift away from calorie counting and toward prioritizing whole, nutrient-rich foods that naturally regulate hunger and energy balance. Rather than viewing GLP-1 drugs as a lifelong solution, they should be seen as a temporary aid, with the ultimate goal of restoring metabolic health through diet and lifestyle interventions.