The Seed Oil Debate Demystified

The tricky thing about science is that it never really proves anything; it only gathers evidence. Nutrition science is particularly tricky because of how much lacks strong evidence. Worse, weak evidence is often dressed up as strong to push agendas or products. Recently, a growing number of nutrition enthusiasts have started fervently opposing the consumption of seed oils (typically marketed as “vegetable oils”). Some experts dismiss this concern, stating that evidence overwhelmingly supports the use of seed oils as both safe and healthy. In the past, most of us would have no choice but to accept these opinions at face value. But, thanks to the beauty of the information age, we can access cutting-edge science with a few clicks from the comfort of our bedrooms. It’s still not always easy to figure things out, but this post distills the science into something simple and clear, so you’ll walk away with a much better understanding of what’s really going on with seed oils.

Why Are Seed Oils Promoted as Healthy?

Seed oils (sunflower, safflower, soybean, canola, corn, etc.), which are rich in omega-6 polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs), consistently lower LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) in the blood compared with saturated fats (SFAs) from meat and dairy. Even critics of seed oils generally accept this as fact. Where debate arises is in interpretation: researchers often extrapolate these results to claim that PUFAs improve heart health. It’s true that, on average, higher LDL-C correlates with higher rates of heart disease. But LDL-C can rise for many reasons: some reflecting genuine metabolic dysfunction, and others more benign. That’s why cardiovascular risk is assessed with multiple markers, not LDL-C alone. Elevation in this single marker, without context, tells only part of the story. So, focusing only on LDL-C to dictate whether or not one should consume seed oils is extremely myopic. I’ll do a deep dive on cholesterol and heart disease in the future, which is why if you’re not already subscribed to these blog updates, you will benefit greatly by doing so right now at the bottom of the page.

LDL cholesterol can rise for many reasons: some reflecting genuine metabolic dysfunction, and others more benign.

The Theoretical Problem With Seed Oils

The theoretical problem with seed oils can be summed up in one word: oxidation. Because PUFAs have multiple unstable carbon-carbon double bonds, they are vulnerable to oxidative damage. These fats can undergo lipid peroxidation when exposed to heat, light, oxygen, or free radicals in the body. Once oxidized, they can propagate chain reactions that damage cells by destabilizing membranes and other vital structures. If you want a more formal scientific understanding of what happens, read about lipid peroxidation.

Even with this well-understood process, theory alone cannot settle the science. On one end of the spectrum, some argue that all dietary PUFAs should be minimized because of their high susceptibility to oxidation, making SFAs the safer choice. On the other end, seed oil proponents emphasize human studies suggesting benefits of replacing SFAs with PUFAs, and claim that the health risks of junk foods containing seed oils stem from other factors. The controversy persists because voices across this spectrum frame the evidence differently, with the loudest extremes amplified by social media. With that landscape in mind, let’s look at what the research actually shows.

The theoretical problem with seed oils can be summed up in one word: oxidation.

Human Trials and Their Limitations

A good science experiment isolates a single variable and determines outcomes based on that variable. If we could recruit a large sample of genetically identical humans and keep them in the same environment for a long period of time, that would be great for research. But, for obvious ethical reasons, we can’t create an army of genetic clones and lock them in a lab for decades. Instead, scientists recruit as many people as financially feasible and practical as possible, with vaguely similar health backgrounds based on a few measurements. A lot of variability is still left on the table. The result is that even if a human study has a clear significant outcome, nuances are usually unaccounted for, and a similar study might even result in a different outcome. Thus, cherry-picking individual studies to support one’s own bias becomes very easy.

Going back to seed oils, the way many human trials involving seed oils are designed are not by substituting one entire dietary pattern with another, but by taking an existing dietary pattern and substituting external sources of fats. What that usually means is finding a bunch of participants and instructing them to substitute SFAs with PUFAs (usually seed oils). In other words, if participants were to spread butter on their bread or sour cream on their baked potato, they would instead be instructed to use a PUFA-rich spread or oil, like in this study. Or perhaps the researchers might provide them with some baked goods that contain a SFA-rich oil versus a PUFA-rich one, demonstrated here. These designs almost always show seed oils in a favorable light because they are being compared to butter, lard, or cream within otherwise standard Western diets. But eating SFAs with a subpar diet is not the same as eating them within a whole-food diet rich in nutrients. Additionally, these studies usually use a small sample size, and the PUFA group almost certainly knows they are in the “healthy” intervention group, which introduces an expectancy bias. Also noteworthy is studies that contradict the prevailing dietary narrative have historically faced more difficulty being published by major organizations like the American Diabetes Association. Finally, participants in these studies usually do not consume oils in their most oxidized forms, which are in packaged and fried foods. Taken together, these caveats help explain why substitution studies can create the impression that SFAs drive disease while seed oils are protective, despite only existing for a negligible fraction of our evolutionary history.

Eating saturated fats with a subpar diet is not the same as eating them within a whole-food diet rich in nutrients.

What Animal Studies Reveal

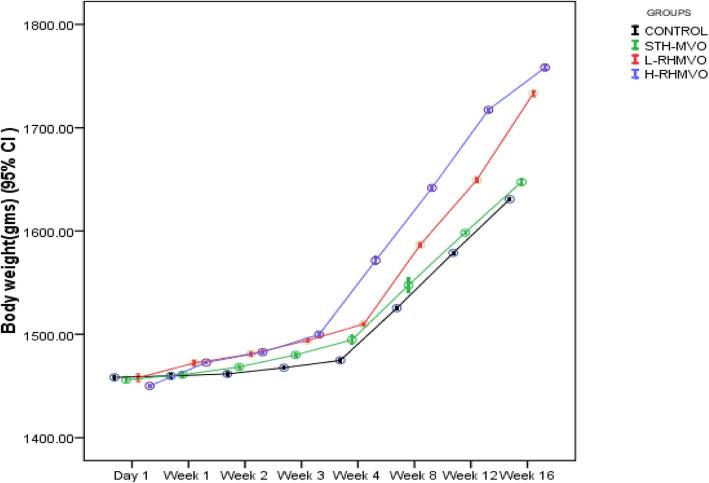

Curious minds often dismiss animal studies because they see a new cure for cancer in mice every week and inherently know that those dramatic results will not likely be replicated in humans. But while every species has its unique biology, humans and other animals are wired similarly in enough ways to gather very interesting findings, albeit with grains of salt. The colossal advantage of animal studies over human ones is that animals can be both genetically programmed and environmentally nurtured identically. That means almost every variable can be controlled for and the result of the experiment is much more reliable, even if not always directly applicable to humans. This study demonstrates the perils of oil oxidation in a way that human studies cannot. Rabbits were fed either a standard diet with no oil, single time heated oil (STHO), or repeated time heated oil (RTHO). Returning to the theoretical problem with seed oils, we’d expect the oil exposed to more heat to cause more damage in the rabbits due to more oxidation. That’s exactly what happened:

Total body weight, liver fat, and oxidative stress were significantly higher in rabbits fed RTHO, despite consuming less food! It’s not a fluke; a similar study was done on rats with similar results. So although rabbits and rats aren’t the same as humans, we can see that oxidized oils may disrupt metabolic signaling beyond calories alone. It fits perfectly with my Oxidative Stress as the Root of Metabolic Disease model. To strengthen that hypothesis, we already observe that in humans, those who consume large amounts of oxidized oil (via ultra-processed food) are more likely to gain weight and experience health issues than those who don’t. On the other hand, the results of STHO-fed animals were similar to that of the control groups, which suggests that normal use of seed oils for home cooking with limited heat exposure might not be as harmful as the anti-seed-oil crowd claims. That’s probably because endogenous antioxidant defense systems can handle some amount of oxidation, so un-oxidized PUFAs from natural foods and moderately-oxidized PUFAs from STHO do not cause the same problems as the extremely-oxidized PUFAs in RTHO. In short, eating oil from ultra-processed/fast food leads to much higher oxidative stress than cooking from home with the same oil, because oil in factory manufacturing or in a deep fryer is exposed to much more heat/light/pressure. But it might also depend on the total oxidative burden in the subject; perhaps STHO could be enough to tip the balance in favor of oxidative stress for people close to their antioxidant defense limits. We don’t really know, which is why I prefer cooking with butter and tallow for their oxidative stability (and great taste).

Un-oxidized polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) from natural foods and moderately-oxidized PUFAs from single-time heated oil do not cause the same problems as the extremely-oxidized PUFAs in repeated time heated oil.

Are Seed Oils Contributing to Colon Cancer?

Incidence of colon cancer has exploded amongst younger adults in recent years. Interestingly, a BMJ study analyzing CRC tumors published late last year made rounds in news headlines, driving speculation that the tumors could be driven by seed oil consumption in ultra-processed foods. In the study, tumors were found to contain significantly higher levels of the PUFA arachidonic acid (AA), its derivatives, and its precursor linoleic acid (LA) than control samples. Because LA is found abundantly in seed oils, the study authors raised the possibility of Western diets high in omega-6 PUFAs contributing to the dysregulated lipid metabolism found in the tumor cells. They are not suggesting that LA and AA are enough to cause cancer on their own, but that high concentrations can sometimes reveal defects in mediators that are supposed to resolve inflammation during the metabolism of these lipids.

Does that mean foods like walnuts or hemp seeds which are high in LA might increase cancer risk? Doubtful, because once again, evidence strongly suggests that it’s the oxidation that matters rather than the simple presence of LA on its own. Normally, the conversion of LA to AA is low, but the conversion increases dramatically when seed oils (which contain lots of LA) are heated. Going back to the BMJ study, we see a coordinated inflammatory signaling cascade:

Of note, genes linked to arachidonic acid lipid production (PLA2G4A and TNF), genes related to pro-inflammatory mediators (ALOX5, ALOX5AP, LTA4H, LTC4S) and their receptors (LTB4R, CYSLTR1, CYSLTR2) all appear to be coordinately expressed along with the inflammatory biomarkers (TGFB1, NFKB1, NFKB2) and associated macrophage markers (CCL2, CCR2) in colon tumours.

We see increased AA production in both the cancer tumors and in a live experiment with consumption of heated oil, supporting the idea that the inflammatory cascade caused by oxidation might be fueling this tumor growth. Here’s where I’ll briefly call out internet misinformation on both sides of the seed oil debate. Some seed oil opponents argue that AA itself is inherently inflammatory and therefore PUFAs should be avoided in favor of SFAs from meat. But this is misleading because AA is actually abundant in meat! During normal metabolism, AA plays essential roles in cell signaling, and increased amounts of it show up incidentally as part of the inflammatory cascade from oxidized LA, but the AA is a symptom and not the cause of the problem. On the other hand, seed oil defenders often stop at saying “LA and AA aren’t inflammatory,” while ignoring the evidence that oxidized LA is. So both seed oil proponents and opponents are missing important pieces of what’s happening, which is why the debate often feels like it’s going in circles.

Tumors were found to contain significantly higher levels of the PUFA arachidonic acid (AA), its derivatives, and its precursor linoleic acid (LA) than control samples.

Silly Quotes From Experts

When I read coverage on seed oils from large news organizations, I often notice that even well-credentialed experts contradict basic nutritional facts. Here are a few standout examples.

It’s true that we eat more ultra-processed junk food than we ever have before, but the evidence is clear that the harms of this kind of food have more to do with their calories and their high amounts of added sugar, sodium and saturated fat than with seed oil.

The sugar criticism is fair, and sodium is contextual, but junk foods are almost always low in saturated fat because their fat comes from seed oils. Even given the extremely strict recommended limit on SFA intake, a diet composed entirely of potato chips would still be under that limit. It’s right on the nutrition label, so why do even highly credentialed experts so often repeat otherwise?

But while some scientists argue that you shouldn’t have too much omega 6 compared to omega 3, [Matti] Marklund says it’s better to up your intake of omega 3 rather than consume less omega 6, as both are associated with health benefits.

— The BBC

The average American consumes 749 calories of seed oil per day. That is an absurd amount of omega-6 PUFA. Omega-3 consumption should increase, but that’s nearly impossible when omega-6 consumption is already extremely high. Even ignoring all oxidation arguments, oil has almost zero nutritional value, so cutting back makes a lot of sense.

We know that ultraprocessed foods generally are not good for your health. They are usually high in sodium or salt, added sugars, unhealthy fats, and additives. That’s why it’s bad for you, not the inclusion of seed oils.

I am curious to know which “unhealthy fats” Matti is talking about, because once again, the fats in ultra-processed foods are almost always exclusively seed oils.

Some of the influencers are talking about getting rid of all the omega-6 in the diet, and that would be a terrible idea. Some omega-6 is absolutely required. The question is how much?

Consuming any source of fat will provide more than enough omega-6 PUFA, because every source of fat contains a mix of different types of fats. Even with a high-SFA carnivore diet, for example, enough omega-6 PUFA is present in the food. Short of consuming no fat at all, which would be deadly, consuming too little omega-6 PUFA is virtually impossible.

Conclusion

Striking correlations between seed oil consumption and disease over the past century aren’t enough on their own to implicate seed oils as a major culprit of declining health. However, controlled trials with oxidized oil support the correlations and present serious concerns. While evidence is not strong enough to conclude that home cooking at reasonable quantities and temperatures within a nutritious diet causes noticeable problems, seed oil defenders tend to focus narrowly on cholesterol and ignore the context in which most seed oils are consumed: deep-fried foods and ultra-processed products where oxidation is highest, pointing fingers at other junk food ingredients instead. They also never mention the huge amount of oil that the average person is already consuming. Furthermore, labeling seed oils as heart-healthy purely for lowering cholesterol reduces “heart-healthy” to a single lab number, while ignoring broader markers of health. Whatever diet one follows, prioritizing fats from whole foods minimizes exposure to oxidation-prone oils and limits the need for added fats of any kind.