The Simple Truth That Will End Your Food Struggles

The main idea I’ve been communicating through these posts is that metabolic problems are not caused by eating too much, but that eating too much is caused by metabolic problems. I’m going to add additional clarification here.

The chain of events that starts these metabolic problems is as follows: poor dietary choices leads to increased oxidative stress, which causes damage to neurons in a region of the brain called the hypothalamus. An inflammatory response kicks off in an attempt to minimize further damage and allow these neurons to repair. As part of this process, protective cells called glia shut down the neuronal response to two very important hormones: insulin and leptin. These hormonal communications are shut off so that the damaged neurons can conserve energy to protect themselves from further stress. An appropriate analogy is to imagine an athlete doing sprints, and he rolls his ankle. Does the athlete keep sprinting, or does he refrain from using his ankle further while he rests and recovers? The same idea applies here at a cellular level.

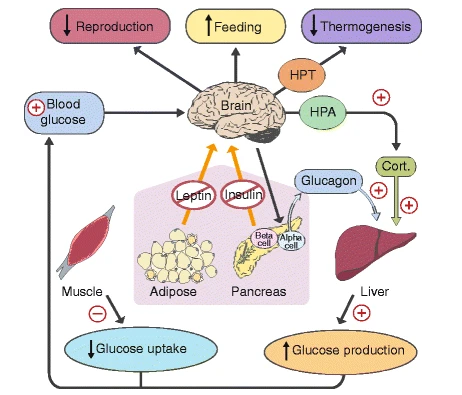

Below is a diagram showing the impact of reduced insulin and leptin response in the hypothalamus:

We already know from decades of research that leptin is essential for satiety signaling, which is why a reduced leptin response leads to increased feeding behavior. But other features of leptin (and insulin) resistance are also made clear. Thermogenesis decreases, meaning the body burns less energy at rest. Cortisol secretion increases, leading to increased glucose production in the liver. Meanwhile, glucose uptake in muscles decreases. The combination of increased glucose production in the liver and decreased glucose uptake in muscles leads to elevated blood glucose, the first step towards hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, and eventually, full-on diabetes. Finally, reproductive function decreases, which can cause other undesirable side effects. The obvious conclusion is that diabetes and many other related illnesses are not caused by obesity, but occur in parallel to obesity as a result of metabolic changes due to poor diet.

Even more interesting than what is happening is why it’s happening. We think of these adaptations as problems because in the modern era of food abundance, none of these effects are particularly desirable. But imagine how useful all of these adaptations are in a starvation state. Increased hunger leads to higher motivation for food-seeking. Decreased thermogenesis and reproduction allows the body to conserve energy. Higher glucose production by the liver and lower glucose uptake by muscles ensures that the most important organ, the brain, has enough glucose to fuel itself. Why would the body mimic a starvation state when food is more abundant than ever? The answer is because in a naturalistic context, oxidative stress can help predict food shortage. Low intake of protein and specific vitamins and minerals leaves the antioxidant defense system weak. With a change in food availability as winter approaches, humans and other mammals may have faced a shortage of these nutrients while energy-dense foods without as many of these nutrients were still available. Biochemical starvation adaptations could have easily made the difference between life and death in a cold, food-scarce winter. Instead of these adaptations occurring after starvation develops, oxidative stress may have allowed time to increase and conserve energy in advance, before most foods were actually scarce.

In the modern context, oxidative stress is rampant in most of the Western population due to high amounts of nutrient-poor refined carbohydrates, high amounts of oxidation-susceptible refined oils, and high amounts of food additives. The solution is not to create strange dietary rules around fats, carbs, or salt, but to maintain a dietary pattern that keeps cellular oxidation balanced. Although only a few effects of metabolic dysfunction were covered here, research is increasingly showing that many other diseases are related. Hypertension, Alzheimer’s, certain cancers, arthritis, mental health issues, eating disorders, and countless other problems have strong ties to metabolic dysfunction. The mechanisms for these ties are still being studied, but by restoring your metabolic health, you may be surprised at how many other problems you inadvertently solve at the same time.